1 year of chorus: behind the searching platform

“1 year of chorus” continues with a technical overview of how I came up with the solution and built upon it. Also briefly what I have in mind for the future to improve upon it.

The basic idea

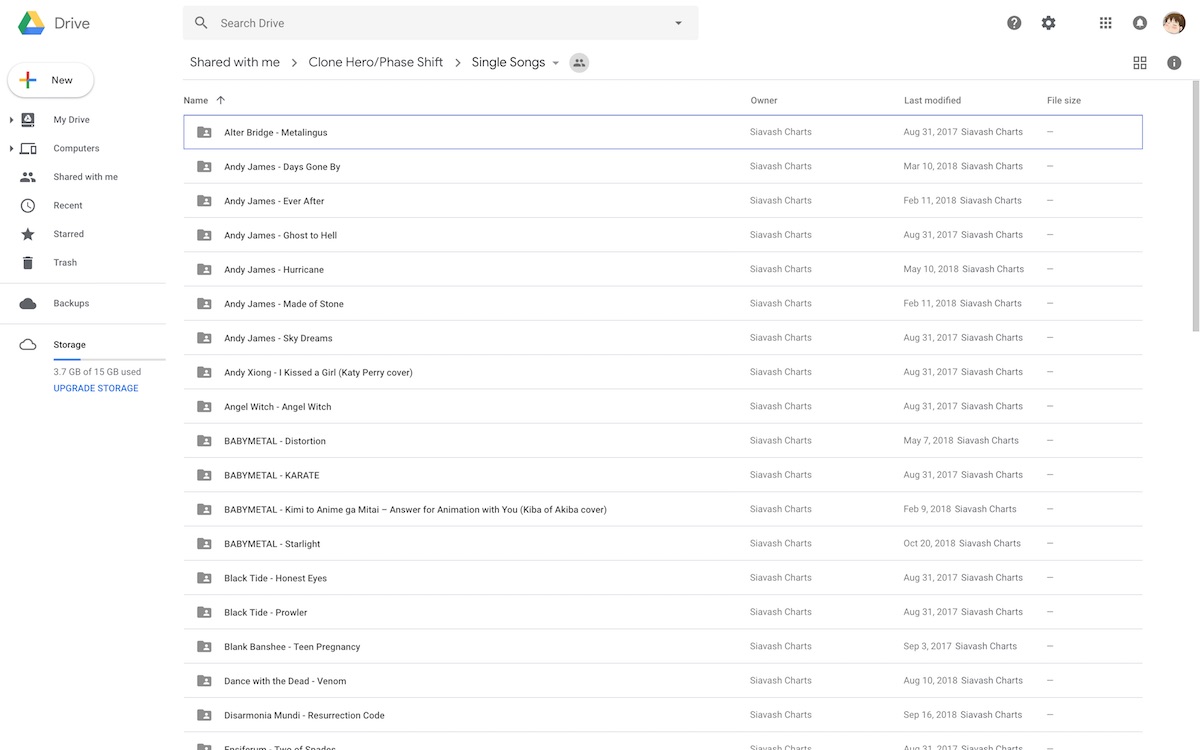

As mentioned in the previous episode, lack of searchability of Google Drive folders is what came to spawn the idea of chorus. Imagine having about 20,000 folders/archives and trying to pick that one song you want from that specific band. Of course you’d want to search through them!

For now, what you have is just a spreadsheet that lists the Google Drive folders of many charters. These are the basic steps I followed to be able to “search through the spreadsheet”:

- Centralize: Have all charters’ folders in one place

- Connect: Be able to access individual chart downloads from this place

- Extract: Pull information about the charts (metadata, notes…) and store them

- Synchronize: Track new charts being added, updated and deleted

- Search: Finally, look for charts!

To perform these steps, we’ll have to figure out a couple of things.

Interacting with Google Drive

The charter drives are stored on Google Drive, so we are going to look at the Google Drive API. An API (Application programming interface) is a “toolbox” that is often provided by platforms and applications of all sorts. This is what is going to enable us to work and interact with Google Drive.

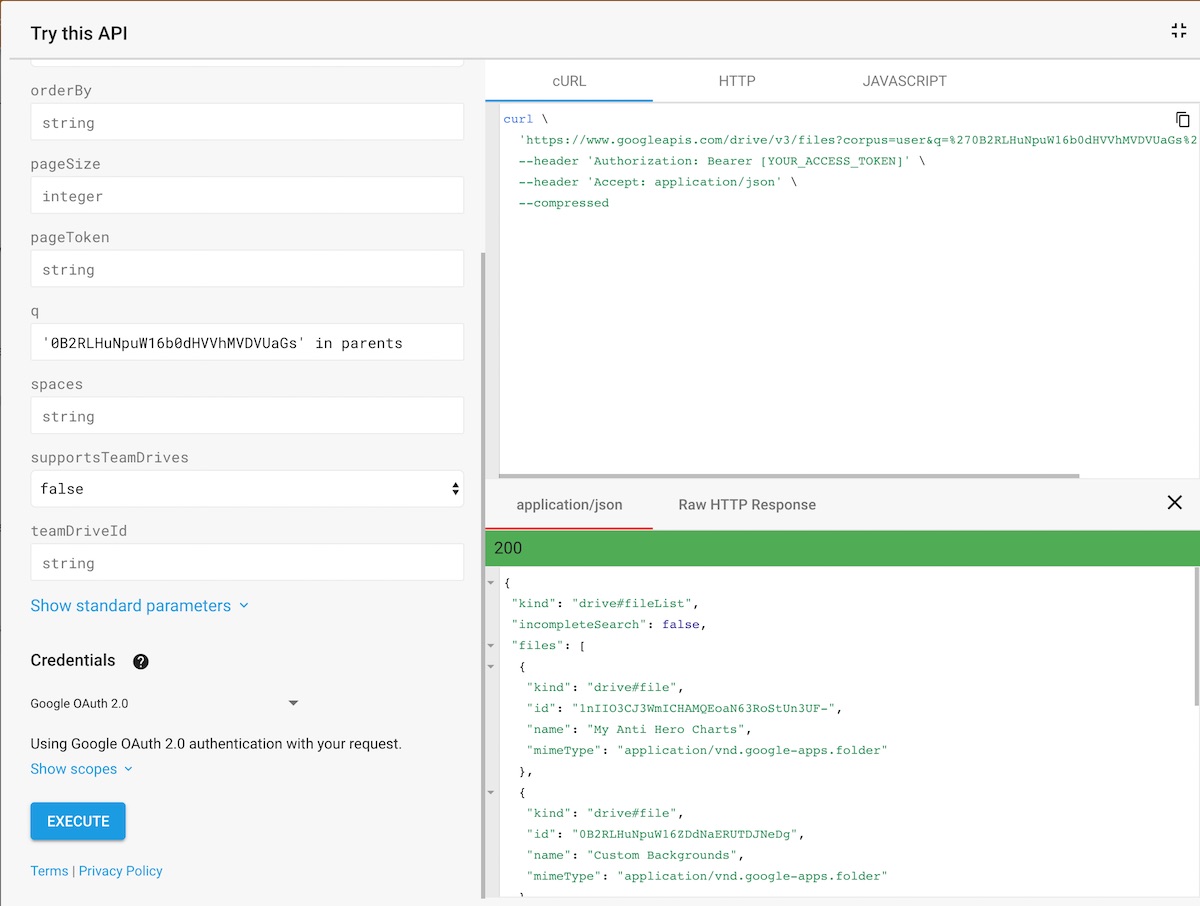

First step is to be able to list the files and folders inside a charter drive, so let’s look at the files.list API. Let’s arm ourselves with a random charter drive. How do we use that?

I’ll spare you the investigation.

Just put '0B2RLHuNpuW16b0dHVVhMVDVUaGs' in parents in the q field, hit “Execute”, log in your account and approve the permissions (don’t worry, you’re basically using a Google app to access Google data).

{

"kind": "drive#fileList",

"incompleteSearch": false,

"files": [

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "1nIIO3CJ3WmICHAMQEoaN63RoStUn3UF-",

"name": "My Anti Hero Charts",

"mimeType": "application/vnd.google-apps.folder"

},

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "0B2RLHuNpuW16ZDdNaERUTDJNeDg",

"name": "Custom Backgrounds",

"mimeType": "application/vnd.google-apps.folder"

},

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "0B2RLHuNpuW16dGFmLTdmcmNLalE",

"name": "Custom Highways",

"mimeType": "application/vnd.google-apps.folder"

},

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "0B2RLHuNpuW16MmFmVlpMTlVBZ1U",

"name": "Packs",

"mimeType": "application/vnd.google-apps.folder"

},

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "0B2RLHuNpuW16UnhnNFUxVXBOamc",

"name": "Single Songs",

"mimeType": "application/vnd.google-apps.folder"

}

]

}What did we just do? We just queried the files and folders that had 0B2RLHuNpuW16b0dHVVhMVDVUaGs (the last part of the folder link, after /folders/, which is the ID of the folder) as their parent folder in all of Google Drive. This is our way of telling the API that we want to see the content of the 0B2RLHuNpuW16b0dHVVhMVDVUaGs folder.

As you can see, it only lists one level of files/folders and it does not look into subfolders. To check subfolders, you have to take a folder you got in the results (for example, let’s take the first one: its ID is 1nIIO3CJ3WmICHAMQEoaN63RoStUn3UF-) and do the same kind of request: '1nIIO3CJ3WmICHAMQEoaN63RoStUn3UF-' in parents.

{

"kind": "drive#fileList",

"incompleteSearch": false,

"files": [

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "1Oa097uRfuWSPP_UEuFSkCwGPV6_8F1s9",

"name": "Wintersun - Sons of Winter and Stars",

"mimeType": "application/vnd.google-apps.folder"

},

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "1A37URXW32g4YZNJgeYcKM6P6lyI7bVTO",

"name": "Wagakki Band - Senbonzakura",

"mimeType": "application/vnd.google-apps.folder"

},

[...]

}Boom, you get another set of files/folders. You continue to do that, over and over again, until you encounter a chart folder. Let’s take the first one: Wintersun - Sons of Winter and Stars, with ID = 1Oa097uRfuWSPP_UEuFSkCwGPV6_8F1s9.

{

"kind": "drive#fileList",

"incompleteSearch": false,

"files": [

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "19QioRM7zqig6ki3v50zMjLE13N3cxl0j",

"name": "vocals.ogg",

"mimeType": "audio/ogg"

},

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "1J7ev3X7C8jkxP54hVqc7NkDIpeXOxnse",

"name": "song.ogg",

"mimeType": "audio/ogg"

},

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "1qd80kBv-rM5vdCh6QVIWJLzSVMfbZPfh",

"name": "rhythm.ogg",

"mimeType": "audio/ogg"

},

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "1dBdwhwa3aeo8ND89uNEDxZ2CGoqb-99h",

"name": "guitar.ogg",

"mimeType": "audio/ogg"

},

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "1_dpTk_rg2eDACvDoE4CR1X8ZZZgpoX3Y",

"name": "drums.ogg",

"mimeType": "audio/ogg"

},

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "1BjspypnoxgSE9EypD_IB_85_cbNCgn-Y",

"name": "bass.ogg",

"mimeType": "audio/ogg"

},

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "1gAZdI3GY18XlpLRI3FLMnVFDk8pU1L3d",

"name": "notes.chart",

"mimeType": "application/octet-stream"

},

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "1mZkg2-Kkk3ZgT-6vKeXPyY3SgTzcLHBT",

"name": "album.png",

"mimeType": "image/png"

},

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "1FQkkZBxfFHr_Vfa6HVbES6YBlPhy8GDN",

"name": "song.ini",

"mimeType": "application/octet-stream"

}

]

}You found it! Since the folder contains at least audio (song.ogg), a chart file (notes.chart) and chart metadata (song.ini), you can say with confidence that this is definitely a song folder that will work with Clone Hero. Take note of the ID of the folder.

A Google Drive folder URL has the following format: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0B2RLHuNpuW16b0dHVVhMVDVUaGs. Notice how the last portion of the URL contains folder IDs. Replace the last part by the ID of the song folder you just found: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1Oa097uRfuWSPP_UEuFSkCwGPV6_8F1s9, and have a look!

You now know how to look inside Google Drive folders, find song folders and get their URLs! Good job!

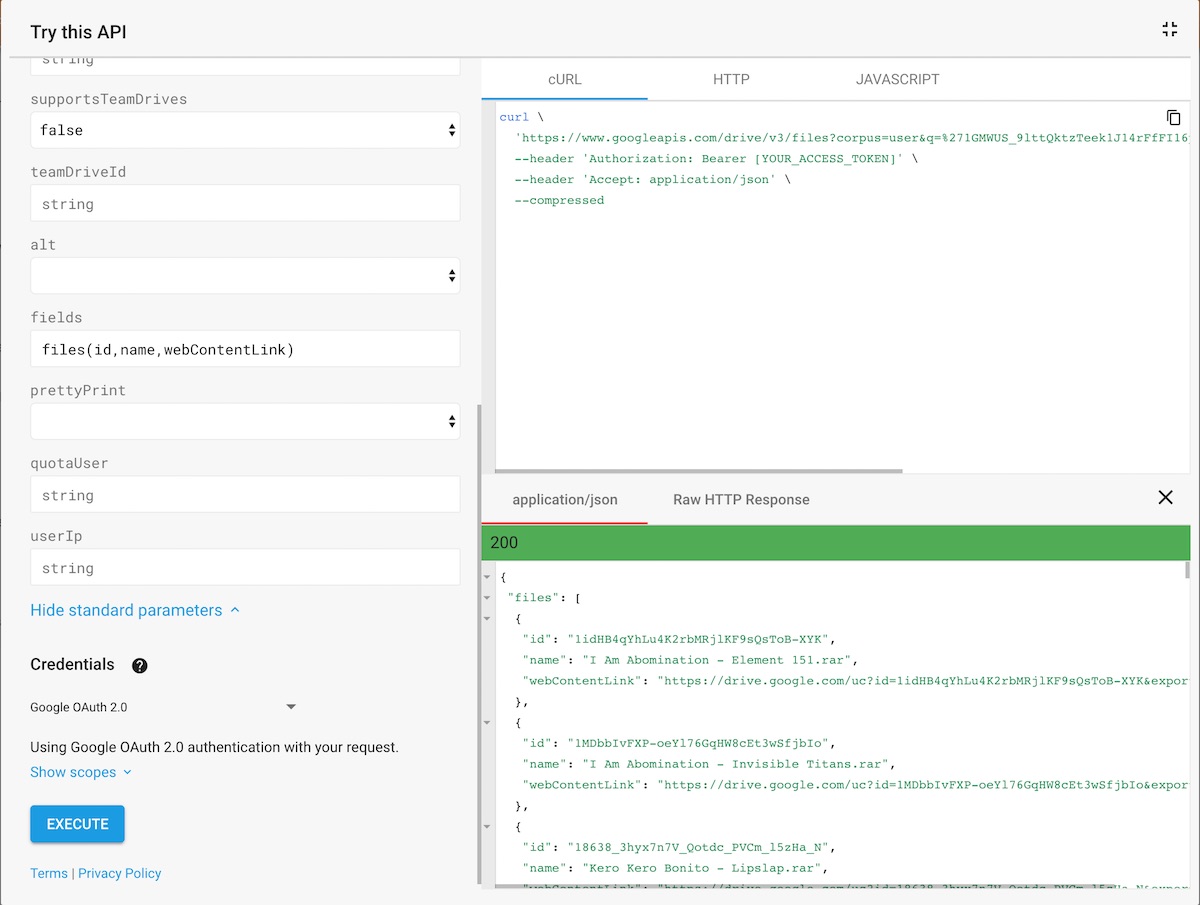

We’re not done yet though, we’re just getting started. Keep in mind people also store their charts in archives! Try '1GMWUS_9lttQktzTeek1J14rFfFI16pFG' in parents.

{

"kind": "drive#fileList",

"nextPageToken": "...",

"incompleteSearch": false,

"files": [

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "1idHB4qYhLu4K2rbMRjlKF9sQsToB-XYK",

"name": "I Am Abomination - Element 151.rar",

"mimeType": "application/rar"

},

{

"kind": "drive#file",

"id": "1MDbbIvFXP-oeYl76GqHW8cEt3wSfjbIo",

"name": "I Am Abomination - Invisible Titans.rar",

"mimeType": "application/rar"

},

[...]

}You cannot look at the contents of an archive without downloading it. Therefore, you just have to flag archives as “potential song downloads”, download them, extract them on your server/computer and check in your local files.

Now how do we reliably get a URL of an archive? It’s not a folder, so the URL replacement we did earlier is not going to work!

There is a way.

Unroll “Show standard parameters” and enter files(id,name,webContentLink) in the “fields”… field. It’s gonna tell the API we want the ID, the name and the link to the webpage of the files/folders we’re getting. Lo and behold, we’re getting some links indeed.

How a program can download a file from Google Drive and extract it locally, I’ll leave that as an exercise to the reader. A little hint though: chorus does extracting with the aid of 7zip, with which you can extract a variety of archives, including the most common ones: rar, zip and 7z.

Anyway, now that we have a strategy to automatically get song URLs, how do we know which URL belongs to which song?

Getting the metadata

Let’s put ourselves back as a Google Drive user. How do we know which song we are downloading? The file or folder name!

A majority of charters use the common accepted convention of Artist/Band - Song Name: we can use that to our advantage to get the artist/band and song name from just a song URL. Cool stuff!

How do you know from which charter you downloaded a chart? If you’re coming from the spreadsheet, you accessed a charter drive through a specific URL which is a Google Drive folder! So from the moment you start iterating through a charter drive, you already know the charter, at least the main one. Bam, that’s more data.

And that was all there was to the very first proof-of-concept of chorus:

- Start from a charter drive

- Iterate through folders and subfolders and find chart folders/archives

- Associate artist/band name and song name, and also attach a charter name to the data if applicable

- Store that data somewhere and provide an interface to it

Really simple. Of course, the real world is more complex: not everyone follows convention. Plus, what about “compilation drives”, such as the Anime Mega Pack? You cannot infer charter names from there!

This is where it starts being interesting relying on where the actual metadata lies: song.ini files. We can download them and take a look at them, since we can get their URLs.

Here’s the content of a song.ini file.

[song]

artist = Queensrÿche

name = The Needle Lies (Live)

frets = Siavash

album = Operation: LIVEcrime

delay = 0

year = 1991

diff_guitar = 3

diff_bass = -1

diff_guitar_coop = -1

diff_rhythm = -1

diff_drums = -1

diff_vocals = -1

diff_keys = -1

diff_bass_real = -1

diff_guitar_real = -1

diff_dance = -1

diff_bass_real_22 = -1

diff_guitar_real_22 = -1

diff_drums_real_ps = -1

diff_keys_real = -1

diff_drums_real = -1

diff_vocals_harm = -1

sysex_open_bass = True

sysex_slider = True

multiplier_note = 116

icon = siavash

charter = Siavash

album_track = 9

genre = Heavy Metal

preview_start_time = 109956

preview_end_time = 139956

song_length = 183293

Seems pretty simple to just pick whatever data you need! We just needed the artist, name and frets/charter data to start with, but while we’re at it (that was my exact thinking at the time), why not store the rest of them and provide them as well?

Not every CH-compatible folder features a song.ini: an audio file and a .chart file are actually enough. There’s actually some metadata inside .chart files too! Usually as the first thing you’ll see.

[Song]

{

Name = "Judgement"

Artist = "Depapepe"

Charter = "Paturages"

Album = "Ciao! Bravo!!"

Year = ", 2006"

Offset = 0

Resolution = 480

Player2 = bass

Difficulty = 0

PreviewStart = 0

PreviewEnd = 0

Genre = "rock"

MediaType = "cd"

MusicStream = "guitar.ogg"

}

It’s a different format, but it’s pretty straightforward still.

There’s plenty of other information you can get besides what’s inside a song.ini or .chart file metadata:

- Amount of notes: count the notes in chart files

- Difficulties/instruments available: check the presence of notes in chart files for respective difficulties/instruments

- Presence of stems: check the presence of audio files named accordingly, e.g.

drums.ogg,rhythm.ogg… - Presence of open notes: check the notes in chart files

- …and so on! The limit is where your mind sets it.

We had fun (probably) fetching our metadata: now we have to store it somewhere!

Storing the data

Where do people store their data? In a database!

chorus made the technical choice of PostgreSQL, a very powerful, jack-of-all-trades relational database that powers hundreds of thousands of platforms all around the web. You probably heard about MySQL, SQLite… maybe even MS SQL. This is the same kind of database.

I won’t be the one to teach you about relational databases, you’ll have to dig yourself if you don’t know about them. But what you need to know is that a database requires structure.

If we represent our database as an Excel spreadsheet, our structure is what will constitute the columns. So naturally, we’re gonna model our columns following the song.ini fields since that’s already laid down for us and it’s neat enough. Add a column for the download link, add another one for the “source folder”, which would be the charter drive you started on, and you’ve got yourself a “mini-chorus”! It might or might not look like this, depending on which columns you decided to pick.

How are we gonna fill our “spreadsheet”? Right now, chorus scans one drive and adds all the found chart links afterwards. This is because inserting songs one by one has overhead: it is faster to deliver a package of 100 brooms in one go than deliver one broom at a time.

It is justifiable as long as the process of getting one chart URL and its metadata is not considerably longer than the process of inserting the data. At first, getting metadata was very fast since it only involved looking at file/folder names. But in the long run, for instance if we decided to download audio files to get their bitrate, the process of downloading multiple chart files from a remote source is going to be much longer than just inserting data to a local database, since you will be dealing with lag, and whatnot.

Therefore, I would like to implement this way of inserting data in chorus in the future, but that would require me to redo and rearrange all of the code that’s involved. But since you don’t have to deal with my code, here are your options: do what sounds better to you!

Searching the data

Looking for a song

You want “Through the Fire and Flames”? Just look for it in the “name” column in the database!

Looking for an artist/band

You want some “Dragonforce”? Just filter according to the “artist” column in the database!

Looking for both!

Now you just want “Through the Fire and Flames” by “Dragonforce” specifically: you can filter through both columns for sure!

…okay, hold on, let’s take a step back. What would you Google to find “Through the Fire and Flames” by “Dragonforce”?

through the fire and flames dragonforce

…now how do you get 2 filters from that? How do you get a “name” filter and an “artist” filter? The answer is “you just can’t”.

But what you can do is create a new column that is “name + artist”. The content of this column is the “name”, followed by a space, followed by the “artist”. And what content do you get for that column for “Through the Fire and Flames” by “Dragonforce”?

Through the Fire and Flames Dragonforce

Of course, you gotta make your search case insensitive, but now we’ve got something that can be matched.

…and more!

flamingo chezy

through the fire and flames guitar hero 3

tenacious d the pick of destiny

All probable search terms you might think of and search for. All affecting different columns. So you might as well build a column combinating all of your searchable columns.

But here’s a good one, how do you match both…

through the fire and flames dragonforce

…and

dragonforce through the fire and flames

Well now that’s a situation. To make it brief, chorus leverages the pg_trgm extension for PostgreSQL, which allows to compute “similarity” scores for any text query. And that’s what’s powering the “quick search” feature of chorus.

It works well enough, but it’s not perfect.

Since we’re matching fields indiscriminately, shorter search terms have higher chances of being ambiguous. For example, for a ghost query, we’d get more songs containing the word “ghost” than songs by the band “Ghost”, which is what we might be looking for. But there’s no simple way to balance proper ponderation because there’s really no telling which field any user might prefer at any point.

As is, if you don’t set a similarity threshold, you’ll get seemingly random results if nothing fits your query. But there’s also no simple way to define such a threshold because the similarity score actually kinda depends on the amount of “words” you stored in your compiled column of all searchable fields.

In fact, the shorter this column is, the higher score it may yield to a query. For example, take the song “Table”, by the artist “Table”, charted by “Table”, featured in the album “Table”. Since it’s all the same word, the only relevant search term and word is really “table”. That explains why you might get this particular result, seemingly randomly, upon searching on chorus.

The advantage of the pg_trgm solution is that you just need PostgreSQL. You’re already using PostgreSQL for storage: if it can deal with loose searching, then let’s go! You have less things to install, less things to deal with, and possibly more resources to work with. But the results will be suboptimal.

Of course, you could just provide “advanced search”: explicitly require the user to fill a “name” field, an “artist” field, etc… but do you really want to make every user process that every time? If you’re having a text field for every searchable column, you’re gonna get bloated really fast. The alternative would just to provide the commonly used ones, but that’s no fun. And it requires me to switch text fields, which loses time.

Welcome to the world of UX. Where every click matters and can make your user love or hate your platform. Feel free to read more about UX, it’s really a fascinating field of work. I’m no expert on it but it’s absolutely central to application development, especially web development.

Looking for a better wheel

Of course, there are libraries, frameworks and platforms that solve these searching issues. I’m gonna name a few that I could be considering migrating chorus to:

- ElasticSearch: The most well-known search engine that powers a lot of platforms’ search features. It’s heavy and full of features, so make sure your server can handle it.

- Xapiand: Apparently a fast, simple and modern search and storage server built for the cloud. Sound pretty good, doesn’t it?

- Typesense: Typo tolerance? That’s a problem I haven’t mentioned, but of course your users are gonna make typos, so that’s useful.

- …and many more!

Of course, you will still have to feed these boys with your data so there’s actually some data to search. But at least you don’t have to worry too much about implementing tons of use cases.

Okay, now you know have a database with some search strategies. Let’s build something anyone can actually use.

Providing an interface

To provide a user interface, you have to build an application. chorus is a web application, or webapp.

You may have heard of HTML, CSS and JavaScript: this is where you’ll use these big boys. chorus makes use of React, a “JavaScript library for building user interfaces” to make my life easier. Actually, it uses Inferno but it’s basically the same thing.

Your server will provide a service that your web page can call to get its information. Just like Google Drive, we will be providing an API to be able to fetch our chart metadata and links.

Our web page lives as an empty shell that is filled by the data fetched from our server. That way, we can separate the concerns of the web page and the concerns of the server-side. We commonly refer to these as the frontend (web page) and the backend (server-side).

What’s even better with the frontend and backend being decoupled is that people can actually implement their own frontends as well! A couple of examples:

- CHSongManager: a desktop application that calls the chorus search API

- spotify-list-to-text: uses the Spotify API to get the list of songs from a playlist and get their charts from chorus using the search API

- HTML embedding

- …and an infinity of use-cases

Sounds cool, doesn’t it? chorus as a webpage is just another frontend among others to interact with the actual search API!

I won’t go into detail on how to implement a whole application: frontend development is a whole beast on its own. But if you do manage to get an interface running, all that’s left to do is to host that somewhere… and you’re done!

Finishing touches

You can add a daily job that scans all the charter drives that you have at your disposition the way you set it up in the previous steps. That way, your database stays up to date. You can speed the process up by not re-processing charts that were not updated: store the modification date and check it whenever you’re syncing.

You’re most likely gonna have to add/remove charter drives to your repertoire of drives. chorus operates on a GitHub based list so I can just pull from it from my server to sync the list, but you can also develop a module to manage that yourself, in your application.

chorus as a search platform gets quite a bit of traffic: it might be valuable to consider advertising stuff that you want to put forward. Therefore, chorus regularly updates its “news” banner with new setlists and releases.

Finally, now that you have a lot of data available, you can also analyse it. How many blue notes were used in all of the charts you stored? How many full difficulty charts are there in your database? You also might want to track downloads, have song ratings, chart reviews, and so on…

But these are stories for another day.

Upcoming next is the analysis of chart files (.chart, .mid, .ini…) and their ties to common charting standards. Basically a special CSC metadata checker blog post!